The origins of gelatin

Long before gelatin derived its name from the Latin gelare – to freeze – a couple of thousand years ago, pre-modern homo sapiens had already worked out the jelly-like stuff produced by cooking animals was highly valuable. About 8000 years ago in fact, according to archeologists.

In an age where making it to ‘old age’ carried few guarantees, our cave-dwelling and later Egyptian ancestors were extracting a primitive form of gelatin by boiling down animal hide and bone to make a ‘collagen or glutin glue’ for clothes, furniture and tools that could be the difference between life and death in harsh climates and living conditions.

The ancient Egyptians also cooked up bone-based broths and discovered certain extractions when cooled could be eaten – probably the first time gelatin was produced as a particular foodstuff.

They may not have known it, but these ancients were conducting a primitive form of what we today know as ‘partially hydrolyzing collagen’.

Using gelatin in food

By the Middle Ages food and nutrition links moved to the fore; gelatin-rich deer antler or calves’ feet broth extracts were being touted for their positive effect on joint health by the medical experts of the period.

The Medieval Period saw the jelly-like extracts that were by-products of cooking various meats become popular, often sweetened and flavored and served as desserts.

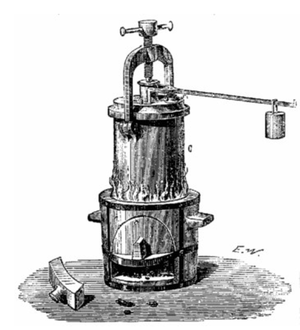

But this process was laborious and thus usually confined to the aristocracy – who could pay servants to do it – until the Renaissance when French mathematician Denis Papin invented the pressure cooker in 1682. The pressure cooker, or ‘digester’ as it was called, meant bones could be boiled down more efficiently to make sheets or leaves of gelatin jelly that could be “used as a general foodstuff for the people” as Papin himself said.

As early as 1754 the first patent for gelatin processing was granted in the UK.

By the Napoleonic wars of the early 1800s, the ‘little general’ himself commissioned research into gelatin’s potential to serve as an alternative protein source for his armies when meat was scarce, which it frequently was during the seemingly endless European wars of that period.

Gelatin use comes of age

Raw collagen-sourced gelatin had come a long way from its origins as a primitive glue but the 19th century really transformed gelatin processing and applications, and saw a legitimate and sizeable industrial age sector emerge.

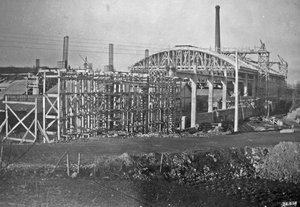

Industrialized gelatin for glue was produced for the first time in Lyon in central eastern France in 1818.

In the pharma world, 1834 saw French chemist Francois Mothes earn a patent for gelatin capsules to mask the bitter flavor of many drugs and medicines and simultaneously protect them from degradation.

In 1847 Londoner James Murdock developed a hard-divided gelatin capsule – but it would be another 50+ years before mass-produced gelatin capsules would revolutionize the pharmaceutical sector with the vast potential of encapsulated powdered medicines.

In food, a US patent was granted for gelatin powder in 1845 that could be used in any kitchen to make gelatin desserts. Half a century later this gelatin form was taken up by the Jell-O firm in New York which became a culinary icon in 20th century America and abroad.

All this meant that by the late 1800s gelatin sheets, leaves, blocks and powders were being mass produced for their adhesive, food and pharma purposes.

Gelatin was proving to be a highly versatile substance, integral to these industries – and new applications were rapidly being discovered.

Around this time, production refinements allowed pure gelatin emulsion plates to help popularize photography (and x-rays) by simplifying what had been an expensive, time-consuming and inconsistent photo development process.

Rousselot was a pioneer in the field, producing multi-purpose, collagen-extracted gelatin sourced from mostly porcine and bovine materials from its newly established French base in the 1890s.

Today in 2021, it is the world’s biggest gelatin supplier.1

20th century: Mass production expands gelatin applications

As the 1900s rolled into view, food applications like lozenges, jellies and gummy bears took advantage of gelatin processing refinements and its unique taste and odor-neutral gelling and thickening properties as economies of scale kicked in after decades of experimentation.

Sales quickly exploded with most of the world’s high-quality gelatin being supplied out of French and German sites.

Supplement, pharma and cosmetic applications exploded too with the likes of gelatin tablets, gelatin capsules, gelatin ointments and gelatin emulsions in the medical and beauty arenas.

US drug maker Eli Lilly, which had been using gelatin in some of its capsules since 1897, debuted the world’s first automated production line for hard gelatin capsules in 1913.

By 1930 soft gelatin capsules were being mass produced by soft-fill machines, and other innovations like gelatin-coated tablets came onstream, further popularizing gelatin use.

Gelatin in war times

Gelatin performed an important role in World War 1 where it was sometimes used as a substitute for intravenous blood-boosting plasma solutions to treat the wounded (plasma was often in short supply2). Many lives were saved with gelatin used in this way.

Gelatin-based capsules and other pharmacologicals were popular in World War 1, and gelatin was used in pills housing everything from morphine and codeine to cocaine and amphetamines – then legal – to treat soldiers and help them deal with the physical and psychological horrors of trench warfare3.

Did you know?

German pharma firm Merck had been selling cocaine legally since 1862. The British Army gave soldiers a gelatine coated cocaine and cola nut concoction called Forced March that was made by Burroughs Wellcome & Co since 1890. Front-of-label marketing stated Forced March ‘Allays hunger and prolongs the power of endurance’.

Gelatin-based jelly babies were popularized when British confectionery maker Bassett’s commemorated the November 1918 World War 1 armistice by releasing Peace Babies.

World War 2 devastated the European gelatin industry with many factories damaged or destroyed in bombing raids, even as demand for photographic gelatin grew due to its strategic importance to military operations.

Gelatin evolves

The gelatin industry quickly recovered post-war and moved into a period of growth in the post-war period which continues to this day with food and food supplements (59%) and pharma (31%) applications remaining dominant4.

Gelatin glue is still popular for certain tasks due to its heating and cooling flexibility and phenomenal strength – up to 1.6 tons per square centimeter. It is a favorite of musical instrument makers and document preservers for instance.

Into this mix an ever-widening array of niche applications is emerging that includes:

Sensitive pharma applications

- plasma substitutes

- surgical sponges

- femoral plugs

- hemostats

- vaccines

- stem cell therapy agents

- in-lab bacteria cages

Technical applications

- forensics gels

- glues for restoring books

- laundry whiteners

- paint binding agents

- plant fertilizers

Novel food applications

- beverage clarifiers

Trade groups have entered the fray to enable the industry to promote collaboration and pool knowledge; develop and communicate science; advocate for appropriate regulations and ensure products of the highest quality are produced.

These include the Gelatine Manufacturers of Europe (GME) in 1974; the Gelatin Manufacturer Association of South America (SAGMA) in 1995; the Gelatine Manufacturers Association of Asia Pacific (GMAP) in 1996 and in recent years the Gelatin Manufacturers Association of Japan (GMJ) and the Gelatin Manufacturers Institute of America (GMIA).

Since July 2020, the four regional gelatin associations have been working together in a joint working group, Gelatin Representatives of the World (GROW), to better represent the gelatin sector on the international stage.

How is gelatin manufactured today?

As this brief gelatin history reveals, gelatin has come a long way over several millennia from cauldron-boiled animal skins and bones to the sophisticated manufacturing sites that define the modern gelatin industry. Fact is, extracting consistently high-quality gelatin from native collagen to meet modern demands is a complex and difficult process. Very few can do it.

Rousselot employs strictly controlled hygienic processes that meet national and international ISO, HACCP and GMP specifications to ensure industry-benchmark, non-GMO, chemical conversion-free gelatin.

This QC and traceability obsession is enacted at every step of the process at Rousselot’s 11 scalable facilities on four continents.to meet requirements whether it is for food, pharma, cosmetic, biomedical or technical applications.

It is this kind of obsession with quality that has fueled 130 years of specialized refinement and innovation Rousselot is proud to add to gelatin’s 8000 year evolution.

And even after all these years, after all these centuries, in 2021, the best thing is there is still so much to discover about the miraculous molecules that make up gelatin.

References:

1 Global Gelatin Market Insights Forecast to 2026, Calibre Research, 2020

3https://encyclopedia.1914-1918-online.net/article/drugs

4 https://www.gelatine.org/en/gelatine/history.html and https://www.gelatine.org/en/applications/specials.html